Historic Valley Forge & Montgomery County

Ready, set, explore!

History is everywhere in Montgomery County. Take a journey back to 1777 and explore the sights and sounds of the Revolutionary War. Follow in George Washington’s footsteps from Valley Forge National Historic Park to the history and heritage woven throughout the towns of Montgomery County.

Feel the stories come to life around you as you tour through the historical homes and parks, then sink deeper into the story as you indulge in historic eats. Discover history like never before. Don't forget to sign-up for the Montco History Pass to explore historical sites and win prizes!

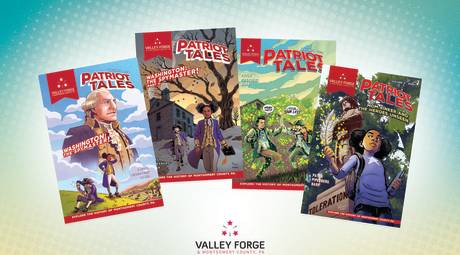

COMIC BOOK SERIES

Are your kids interested in history? Then, download the Patriot Tales comic book series! The story follows two kids who time travel and meet George Washington on a historical adventure!

INDULGE IN HISTORIC EATS

The culinary offerings of Montgomery County have greatly expanded since the days of the Valley Forge encampment. Today you will find everything from fine dining to fast food, 250-year-old taverns to modern restaurants with dishes inspired by the flavors of Asia, Europe and the Americas. No matter your taste, you will find plenty to satisfy you during your visit.

LIVE THE STORY

Journey back to a time of patriots and loyalists, citizens and soldiers, historic homes and battlefields, villages and hamlets. Montgomery County bore witness to pivotal events in the British campaign to capture Philadelphia in 1777, ultimately leading to the Continental Army's famous winter encampment at Valley Forge. Immerse yourself in this rich story and see history come alive around you.

GET THE FREE MONTCO HISTORY PASS

Explore history in a whole new way!

Make sure you get the FREE The Montco History Pass before you visit the Valley Forge National Historical Park. While here, check-in on the app and earn points to late redeem for a prize! The Montco History Pass will lead you on a journey as you explore historical homes, parks, and museums throughout Valley Forge and Montgomery County, PA, honoring the Revolutionary War and early Pennsylvania history. There are 17 historical sites included in this pass that can be explored all year long!

Montco History Pass Locations

Start exploring historical Valley Forge and Montgomery County today!