Despite being only nine years old, Rian Reed is getting ready to drive Fayette Street in Conshohocken.

She will be in a car with no headlights, no turn signals, no windshield wipers and no license plate.

Despite all that, she will not be ticketed.

Reed is one of the more than 30 competitors in the 66th annual Conshohocken Soap Box Derby on July 4.

The first heat begins at 9 a.m. on a course that stretches nearly 1,000 feet on Fayette, from Eighth Avenue to a hay-baled finish line between Fifth and Sixth.

This year's event marks Reed's debut, but the desire to race down Conshy's infamous hill rests deep in her DNA. Her father, Rob, competed in the 1980s, and his uncle was a winner in the mid-1960s.

The love of the race and its pass-down from generation to generation is also what looped in Mark Marine. He has been local/regional race director for 16 years.

"My niece started racing in 1988," Marine says. "So I helped my brother-in-law with the car and all that. Then my son started racing in 1989. And my daughter got into it in 1995. In 2000, the acting race director stepped down, and I was asked to take over."

Marine recalls when the entries were a little more wild and wooly than they are now.

"Back in the 1990s, the All-American Soap Box Derby (AASBD) started providing kits, so that assembling the cars could be standardized and made safer," Marine explains. "But before that, they supplied blueprints, and racers got their own material - plywood and things like that."

In the annals of soap box history, the sport's 1930s beginnings included scrap wood, sheet tin and baby buggy wheels. The name "soap box derby" meant literally that: vehicles made from the wooden crates once used to ship soap.

Now, racers must submit to a number of inspections, ensuring that their cars are structurally sound, reflect no illegal construction techniques and adhere to the strict weight maximum of 200 pounds for both car and rider.

The parent-child collaboration, for Marine, explains how the derby has endured.

"It's one of the last family-oriented sports still around," he comments. "I always say it's not a ‘drop-off sport' where teams fill up in the morning and parents can come get and get their kids in the early afternoon. I mean, as a parent, you're involved."

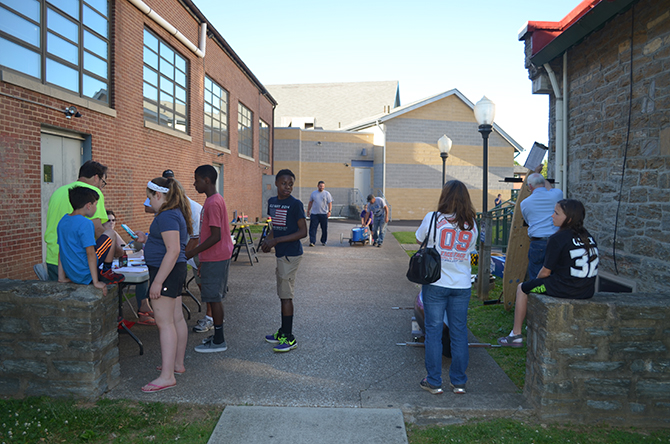

On a mid-June evening, Rian and her dad report for inspection.

Once the sleek fiberglass shell has been taken off her car, Leo, a volunteer whose checklist is snapped into place by a clipboard, peers at the results of her work.

"We started working on this in April, in the garage," Rob Reed says, as his daughter Rian's handiwork is examined. "It didn't take long. It was fun to work on together. We've done a few test runs, and she's ready."

Rian cites her inspiration for naming her car. "I like the Road Runner," she says, grinning.

Leo measures the length, checks the bolts and finds everything in compliance. "This is a clean-looking car," he summarizes. "It looks good."

Rian accepts the compliment and she and her father begin reattaching the chassis.

Leo moves onto the next racer.

The Conshohocken Soap Box Derby is, according to Marine, the only race in the country still scheduled for July 4. This year, the Republican National Convention in Cleveland almost interfered with the local tradition, but Marine leveraged some wiggle room.

"The winners here go onto compete in Akron on July 16, and with the convention in Cleveland, the AASBD wanted all qualifying rounds completed by July 2," he related.

"I called and said I needed some sort of extension. I told them, ‘Let me have my race on the fourth.'

"They agreed, saying, ‘We're not going to make you move. We'll let you have it on the fourth.'

"So I have a special dispensation."